That fascination with those left-right halves, on the part of both the lay and scientific populace, is nothing really new. It is a symptom of how we acquire various pairs of words that each divide some aspect of the world into opposing poles.

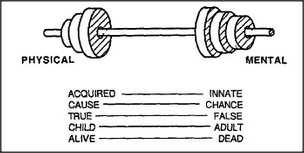

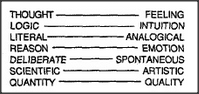

Such divisions all have flaws, but often give us useful ways to think. Dividing things in two is a good way to start, but one should always try to find at least a third alternative. If one cannot, one should suspect that there may not be two ideas at all, but only one, together with some form of opposite. A serious problem with these two-part forms is that so many of them are so similar. This leads us into making false analogies. Consider how the pairs below, in which each self is neatly split into two parts, lead everyone to think they share some common unity.

The items on the left are seen as neutrally objective and mechanical, and only found within the head. We think of Thought and its associates as accurate, but rigid and insensitive. The items on the right are seen as matters of the heart — as vital, warm, and individual; we like to believe that Feeling is the better judge of the things that ought to matter most. Cool Reason, by itself, seems too impersonal, too far from flesh; Emotion lies much closer to the heart, but it, too, can be treacherous, through growing so intense that reason gets completely overwhelmed.

How marvelous this metaphor! How could it work so well, unless it had some basic truth? But wait: whenever any simple idea appears to explain so many things, we must suspect a trick. Before we're drawn into dumbbell schemes, we owe it to ourselves to try to understand their strange attractiveness, in order that we not be deceived, as Wordsworth said, by

. . . some false secondary power, by which, In weakness, we create distinctions, then Deem that our puny boundaries are things Which we perceive, and not which we have made.