Let's do one more experiment: touch one ear and then touch your nose. They don't feel very similar. Now touch one ear and then the other. These touches seem more similar, although they're twice as far apart. This may be in part because they are represented in related agencies. In fact, our brains have many pairs of agencies, arranged like mirror- images, with huge bundles of nerves running between them.

The two hemispheres of the brain look so alike that they were long assumed to be identical. Then it was found that after those cross-connections are destroyed, usually only the left brain can recognize or speak words, and only the right brain can draw pictures. More recently, when modern methods found other differences between those sides, it seems to me that some psychologists went mad — and tried to match those differences to every mentalistic two-part theory that ever was conceived. Our culture soon became entranced by this revival of an old idea in modern guise: that our minds are meeting grounds for pairs of antiprinciples. On one side stands the Logical, across from Analogical. The left-side brain is Rational; the right side is Emotional. No wonder so many seized upon this pseudoscientific scheme: it gave new life to nearly every dead idea of how to cleave the mental world into two halves as nicely as a peach.

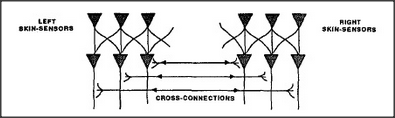

What's wrong with this is that each brain has many parts, not only two. And though there are many differences, we also ought to ask about why those left-right brain halves are actually so similar. What functions might this serve? For one thing, we know that when a major brain area is damaged in a young person, the mirror region can sometimes take over its function. Probably even when there is no injury, an agency that has consumed all the space available in its neighborhood can expand into the mirror region across the way. Another theory: a pair of mirrored agencies could be useful for making comparisons and for recognizing differences, since if one side could make a copy of its state on the other side then, after doing some work, it could compare those initial and final states to see what progress had been made.

My own theory of what happens when the cross-connections between those brain halves are destroyed is that, in early life, we start with mostly similar agencies on either side. Later, as we grow more complex, a combination of genetic and circumstantial effects lead one of each pair to take control of both. Otherwise, we might become paralyzed by conflicts, because many agents would have to serve two masters. Eventually, the adult managers for many skills would tend to develop on the side of the brain most concerned with language because those agencies connect to an unusually large number of other agencies. The less dominant side of the brain will continue to develop, but with fewer administrative functions — and end up with more of our lower-level skills, but with less involvement in plans and higher-level goals that engage many agencies at once. Then if, by accident, that brain half is abandoned to itself, it will seem more childish and less mature because it lags so far behind in administrative growth.