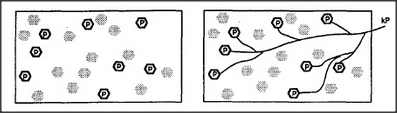

Suppose once, long ago, you solved a certain problem P. Some of your agents were active then; others were quiet. Now let's suppose that a certain learning process caused the agents that were active then to become attached to a certain agent kP, which we'll call a K-line. If you ever activate kP afterward, it will turn on just the agents that were active then, when you first solved that problem P!

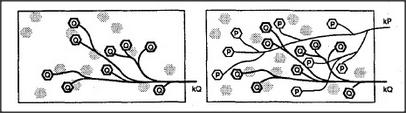

Today you have a different problem. Your mind is in a new state, with agents Q aroused. Something in your mind suspects that Q is similar to P — and activates kP.

Now two sets of agents are active in your mind at once: the Q-agents of your recent thoughts and the P-agents aroused by that old memory. If everything goes well, perhaps both sets of agents will work together to solve today's problem. And that's our simplest concept of what memories are and how they're formed.

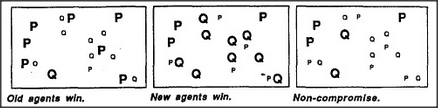

What happens if the now active agents get into conflicts with those the K-line tries to activate? One policy might be to give priority to the K-line's agents. But we wouldn't want our memories to rearouse old states of mind so strongly that they overwhelm our present thoughts — for then we might lose track of what we're thinking now and wipe out all the work we've done. We only want some hints, suggestions, and ideas. Another policy would give the presently active agents priority over the remembered ones, and yet another policy would suppress both, according to the principle of noncompromise. This diagram shows what happens for each of these policies if we assume that neighboring agents tend to get into conflicts:

The ideal scheme would activate exactly those P 's that would be most helpful in solving the present problem. But that would be too much to ask of any simple strategy.