Whenever we talk about a goal, we mix a thousand meanings in one word. Goals are linked to all the unknown agencies that are engaged whenever we try to change ourselves or the outside world. If goal involves so many things, why tie them all to a single word? Here's some of what we usually expect when we think that someone has a goal:

A goal-driven system does not seem to react directly to the stimuli or situations it encounters. Instead, it treats the things it finds as objects to exploit, avoid, or ignore, as though it were concerned with something else that doesn't yet exist. When any disturbance or obstacle diverts a goal-directed system from its course, that system seems to try to remove the interference, go around it, or turn it to some advantage.

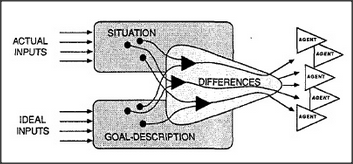

What kind of process inside a machine could give the impression of having a goal — of purpose, persistence, and directedness? There is indeed a certain particular type of machine that appears to have those qualities; it is built according to the principles below, which were first studied in the late 1950s by Allen Newell, C. J. Shaw, and Herbert A. Simon. Originally, these systems were called general problem solvers, but I'll simply call them difference-engines.

A difference-engine must contain a description of a desired situation. It must have subagents that are aroused by various differences between the desired situation and the actual situation. Each subagent must act in a way that tends to diminish the difference that aroused it.

At first, this may seem both too simple and too complicated. Psychologically, a difference-engine might appear to be too primitive to represent the complex of ambitions, frustrations, satisfactions, and disappointments involved in the pursuit of a human goal. But these aren't really aspects of our goals themselves but emerge from the interactions among the many agencies that become engaged in pursuit of those goals. On the other side, one might wonder whether the notion of a goal really needs to engage such a complicated four-way relationship among agents, situations, descriptions, and differences. Presently we'll see that this is actually simpler than it seems, because most agents are already concerned with differences.