We'll now see how frames can help to explain how we understand that children's tale. How do we know that the kite is a present for Jack — when neither sentence mentioned this?

Mary was invited to Jack's party. She wondered if he would like a kite.

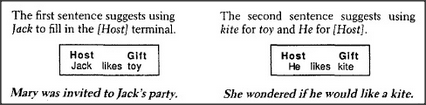

After the first sentence activates a party-invitation frame, the reader's mind remains engaged with that frame's concerns — including the question of what type of birthday gift to bring. If this concern is represented by some subframe, what are the concerns of that subframe? That present must be something that will please the party host. Toy would be a good default for it, since that's the most usual kind of gift for a child.

Since Jack is a he and a kite is a toy, these two frames will merge perfectly — provided that the reader's frame for boy assumes that Jack is likely to enjoy kites. Then our two sentences combine perfectly to fill the present frame's terminals, and our problem is solved!

What makes a story comprehensible? What gives it coherency? The secret lies in how each phrase and sentence stirs frames into activity or helps already active ones to fill their terminals. When the first sentence of our story mentions a party, various frames are excited — and these are still active in the reader's mind when the next sentence is read. The ground is prepared for understanding the second sentence because so many agents are already ready to recognize possible references to presents, clothes, and other matters that might be related to birthday parties.