Imagine that you turned around and suddenly faced an absolutely unexpected scene. You'd be as shocked as though the world had changed before your eyes because so many of your expectations were not met. When we look about a familiar place, we know roughly what to expect. But what does expect mean?

Whenever we become familiar with some particular environment like an office, home, or outdoor place, we represent it with a frame-array whose terminals have already been filled. Then, for each direction of motion inside that environment, our vision-systems activate the corresponding frames of that array. We also activate the corresponding frames even when we merely consider or imagine a certain body motion — and this amounts to knowing what to expect. In general, each frame of a spatial frame-array is controlled by some direction-neme. However, in surroundings that are either especially familiar or whose relationships we do not understand, we may learn to use more specific stimuli instead of using direction-nemes to switch the frames. For example, when you approach a familiar door, the frame for the room that you expect to find behind that door might be activated, not by your direction of motion, but by your recognition of that particular door. This could explain how a person can reside in the same home for decades, yet never learn which of its rooms share common walls.

In any case, all this is oversimplified. Many of our frame-arrays must require more than nine direction views; they need machinery to modify the sizes and shapes of their objects; they must be adapted to three dimensions; and they must be able to represent what happens at intermediate moments during motion from one view to another. Furthermore, the control of frame selection cannot depend on a single, simple set of direction-nemes, for we must also compensate for the motions of our eyes, neck, body, and legs. Indeed, a major portion of our brain-machinery is involved with such calculations and corrections, and it takes a long time to learn to use all that machinery. The psychologist Piaget found that it takes ten years or more for children to refine their abilities to imagine how the same scene will appear from different viewpoints.

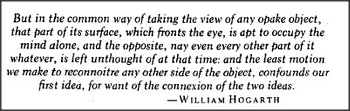

This was the basis of Hogarth's complaint. The artist felt that many painters and sculptors never learned enough about spatial transformations. He felt that mental imagery is an acquired skill, and he scolded artists who gave too little time to perfecting the ideas they have in their minds about the objects in nature. Accordingly, Hogarth worked out ways to train people to better predict how viewpoints change appearances.

[He who undertakes the acquisition of] perfect ideas of the distances, bearings, and oppositions of several material points and lines in even the most irregular figures, will gradually arrive at the knack of recalling them into his mind when the objects themselves are not before him — and will be of infinite service to those who invent and draw from fancy, as well as to enable those to be more correct who draw from the life.