When you think about an object in a certain place, many different processes go on inside your mind. Some of your agencies know the visual direction in which that object lies, others can direct your hand to reach toward it, and yet other agencies anticipate how it would feel if it touched your skin. It is one thing to know that a block has flat sides and right angles, another to be able to recognize a block by sight, and yet another to be able to shape your hand to grasp that shape or recognize it from feeling it in your grasp. How do so many different agencies communicate about places and shapes?

No one yet knows how shapes and places are represented in the brain. The agencies that do such things have been evolving since animals first began to move. Some of those agencies must be involved with postures of the arm and hand, others must represent what we discover from the images inside our eyes, and yet others must represent the relations between our bodies and the objects that surround us.

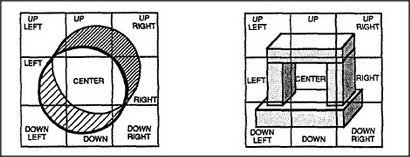

How can we use so many different kinds of information at once? In the following sections I'll propose a new hypothesis to deal with this: that many agencies inside our brains use frames whose terminals are controlled by interaction-square arrays. Only now we'll use those square-arrays not to represent the interactions of different causes, but to describe the relations between closely related locations. For example, thinking of the appearance of a certain place or object would involve arousing a squarelike family of frames, each of which in turn represents a detailed view of the corresponding portion of that scene. If we actually use such processes, this could explain some psychological phenomena.

If you were walking through a circular tube, you could scarcely keep from thinking in terms of bottom and top and sides — however vaguely their boundaries are defined. Without a way to represent the scene in terms of familiar parts, you'd have no well-established thinking skills to apply to it.

The diagram is meant to suggest that we represent directions and places by attaching them to a special set of pronome-like agents that we shall call direction-nemes. Later we'll see how these might be involved in surprisingly many realms of thought.