It is important for us to be able to notice differences. But this seemingly innocent requirement poses a problem whose importance has never been recognized in psychology. To see the difficulty, let's return to the subject of mental rearrangements. Let's first assume that the problem is to compare two room-arrangement descriptions represented in two different agencies: agency A represents a room that contains a couch and a chair; agency Z represents the same room, but with the couch and chair exchanged.

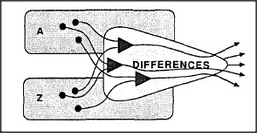

Now if both agencies are to represent furniture arrangements in ways that some third agency D can compare, then the difference- detecting agency D must receive two sets of inputs that match almost perfectly. Otherwise, every other, irrelevant difference between the outputs of A and Z would appear to D to be differences in those rooms — and D would perceive so many spurious differences that the real ones would be indiscernible!

The Duplication Problem. The states of two different agencies cannot be compared unless those agencies themselves are virtually identical.

But this is only the tip of the iceberg, for it is not enough that the descriptions to be compared emerge from two almost identical agencies. Those agencies must, in turn, receive inputs of near identical character. And for that to come about, each of their subagencies must also fulfill that same constraint. The only way to meet all these conditions is for both agencies — and all the subagencies upon which they depend — to be identical. Unless we find another way, we'll need an endless host of duplicated brains!

This duplication problem comes up all the time. What happens when you hear that Mary bought John's house? Must you have separate agencies to keep both Mary and John in your mind at once? Even that would not suffice, for unless both person-representing agencies had similar connections to all your other agencies, those two representations of persons would not have similar implications. The same kind of problem must arise when you compare your present situation with some recollection or experience — that is, when you compare how you react to the two different partial states of mind. But to compare those two reactions, what kind of simultaneous machinery would be needed to maintain both momentary personalities? How could a single mind hold room for two — one person old, the other new?