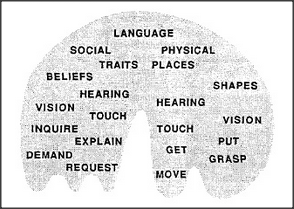

The diagram below depicts a connection-scheme that permits many agents to communicate with one another, yet uses surprisingly few connection wires. It was invented by Calvin E. Mooers in 1946, before the modern era of computers. Here is how we could use just ten wires to enable any of several hundred transmitting-agents to activate any of a similar number of receiving-agents. The trick is to make each transmitting-agent excite not one, but five of those wires, chosen at random from the available ten. Then each receiving-agent is provided with an AND-agent connected to recognize the same five-wire combination.

In this example, each receiving-agent is aroused by precisely one transmitting-agent. If we wanted each receiving-agent to respond to several transmitting-agents, we could join together several separate recognizers so that the receiving-agent's input looks like a tree with a recognizer at the tip of each branch. How could those receivers learn which input patterns to recognize? One way would be to use the kind of evidence-weighing machinery we described earlier. Indeed, for brain cells that would seem quite plausible, since a typical brain cell actually has a treelike network to collect its input signals. No one yet knows quite what those networks do, but I wouldn't be surprised if many of them turn out to be simple Perceptron-like learning machines.

The network shown in the diagram above has a serious deficiency: it can transmit only one signal at a time. The problem is that if several transmitting-agents were aroused at once, almost all ten connecting wires would be activated, which would then arouse all the receiving-agents and cause an avalanche. However, we can make that problem disappear by providing the system with enough additional connection wires. For example, suppose there were ten thousand connection wires rather than ten, and that each transmitting-agent became attached to about fifty of them. Then, even if one hundred agents were to send their signals all at once, there would be less than one chance in a trillion that this would erroneously activate any particular receiving-agent!