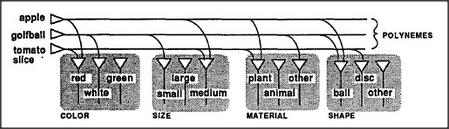

What happens when a single agent sends messages to several different agencies? In many cases, such a message will have a different effect on each of those other agencies. As I mentioned earlier, I'll call such an agent a polyneme. For example, your word-agent for the word apple must be a polyneme because it sets your agencies for color, shape, and size into unrelated states that represent the independent properties of being red, round, and apple-sized.

But how could the same message come to have such diverse effects on so many agencies, with each effect so specifically appropriate to the idea of apple? There is only one explanation: Each of those other agencies must already have learned its own response to that same signal. Because polynemes, like politicians, mean different things to different listeners, each listener must learn its own, different way to react to that message. (The prefix poly- is to suggest diversity, and the suffix -neme is to indicate how this depends on memory.)

To understand a polyneme, each agency must learn its own specific and appropriate response. Each agency must have its private dictionary or memory bank to tell it how to respond to every polyneme.

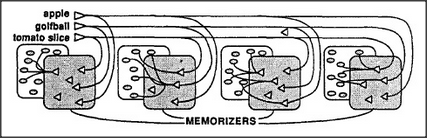

How could all those agencies learn how to respond to each polyneme? If each polyneme were connected to a K-line in each agency, each of those K-lines would need only to learn what partial state to arouse inside its agency. The drawing below suggests that those K-lines could form little memorizers next to the agencies that they affect. Thus, memories are formed and stored close to the places where they are used.

Can any simple scheme like this give rise to all the richness of the meaning of a real language-word? The answer is that all ideas about meaning will seem inadequate by themselves, since nothing can mean anything except within some larger context of ideas.