When life walls us in, our intelligence cuts an opening, for, though there be no rememdy for an unrequited love, one can win release from suffering, even if only by drawing from the lessons it has to teach. The intelligence does not recognize in life any closed situations without an outlet. —Marcel proust

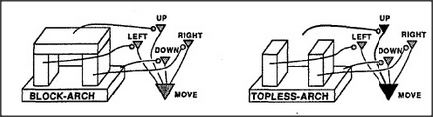

How do boxes keep things in? Geometry is a fine tool for understanding shapes, but alone, it can't explain the Hand-Change mystery. For that, you also have to know how moving works! Suppose you pushed a car through that Block-Arch. Your arm would be imprisoned until you pulled it out. How can you comprehend the cause of this? The diagram below depicts an agency that represents the several ways an arm can move inside a rectangle. The top-level agent Move has four subagents: Move-Left, Move-Right, Move-Up, and Move-Down. (As before, we'll ignore the possibility of moving in and out, in three dimensions.) If we connect each of these sub-agents to the corresponding side of our four-sided box frame, each agent will be able to test whether the arm can move in the corresponding direction (by seeing whether there is an obstacle there). Then, if every direction is blocked, the arm can't move at all — and that's what we mean by being trapped.

The ---o symbol indicates that each box-frame agent is connected to inhibit the corresponding subagent of Move. An obstacle to the left puts Move-Left into a can't-move state. If all four obstacles are present, then all four box-frame agents will be activated; this will inhibit all of Move's agents — which will leave Move itself in a can't-move state — and we'll know that the trap is complete.

However, if we saw a Topless-Arch, then the Move-Up agent would not be inhibited, and Move would not be paralyzed! This suggests an interesting way to find an escape from a Topless-Arch. First you imagine being trapped inside a box-frame — from which you know there's no escape. Then, since the top block is actually missing, when your vision system looks for actual obstacles, there will be no signal to inhibit the Move-Up agent. Accordingly, Move can activate that agent, and your arm will move upward automatically to escape!

This method has a paradoxical quality. It begins by assuming that escaping is impossible. Then this pessimistic mental act — imagining that one's arm is trapped — leads directly to finding a way out. We usually expect to solve our problems in more positive, goal-directed ways, by comparing what we have with what we wish — and then removing the differences. But here we've done the opposite. We compared our plight, not with what we want, but with a situation even worse — the least desirable antigoal. Yet even that can actually help, by showing how the present situation fails to match that hopeless state. Which strategy is best to use? Both depend on recognizing differences and on knowing which actions affect those differences. The optimistic strategy makes sense when one sees several ways to go — and merely has to choose the best. The pessimistic strategy should be reserved for when one sees no way at all, when things seem really desperate.