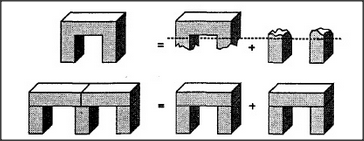

Sometimes when we watch a scene, the wholes we see add up exactly to the sum of their separate parts. But other times, we do not mind if certain things get counted twice. In the first figure below, we divide an arch into body and support with no concern that both parts have exactly the same boundaries. In the second figure, we seem to see two complete arches, despite the fact that there aren't enough legs to make two separate arches.

Sometimes it is vital to keep track, to count each thing exactly once. But in other situations, no harm will come from counting twice. It is efficient to use the same block twice when making viaducts for roads for cars. But if we tried to use the same five blocks to build two separate bridges, we'd end up short. Different kinds of goals require different styles of description. When we discussed the concept of More, we saw how each child must learn when to describe things in terms of appearance and when to think in terms of past experience. The double-arch problem also offers a choice of description styles. If you plan to build several separate things, you'd better keep count carefully or take the risk of running out of parts. But if you do that all the time, you'll miss your chance to make one object serve two purposes at once.

We could also formulate this as a choice between structural and functional descriptions. Suppose we tried to make a match between the structural elements of the double-arch and those of two separate block-arches. In one way to do that, we would first assign three blocks to each arch — and then verify that each arch consists of a top supported by two blocks that do not touch. Then, of course, we'll only find a single three-block arch. There isn't any second arch, since there are only two blocks left.

On the other hand, we could base our description of the double-arch scene on the more functional body-support style of description. According to that approach, we must focus first on the most essential parts. The most essential part of an arch is its top block — and we do indeed find two blocks that could serve as top blocks. Then we need only verify that each of them is supported by two blocks that do not touch — and this is indeed the case. In a function-oriented approach, it seems natural to count carefully the most essential elements, but merely to verify that the functions of the auxiliary elements will somehow be served. The functional type of description is easier to adapt to the purposes of higher-level agencies. This doesn't mean that functional descriptions are necessarily better. They can make it hard to keep track of real constraints; hence they have a certain tendency to lead toward overoptimistic, wishful thought.