What will our portrait-drawing child try next? Some children keep working to improve their person pictures. But most of them go on to put their newfound skills to work at drawing more ambitious scenes in which two or more picture-people interact. This involves wonderful problems about how to depict social interactions and relationships — and these more ambitious projects lead the child away from being concerned with making the pictures of the individual more elaborate and realistic. When this happens, the parent may feel disappointed at what seems to be a lack of progress. But we should try to appreciate the changing character of our children's ambitions and recognize that their new problems may be even more challenging.

This doesn't mean that drawing learning stops. Even as those children cease to make their person pictures more elaborate, the speed at which they draw them keeps increasing, and with seemingly less effort. How and why does this happen? In everyday life, we take it for granted that practice makes perfect, and that repeating and rehearsing a skill will, somehow, automatically cause it to become faster and more dependable. But when you come to think of it, this really is quite curious. You might expect, instead, that the more you learned, the slower you would get — from having more knowledge from which to choose! How does practice speed things up?

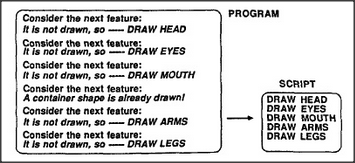

Perhaps, when we practice skills we can already perform, we engage a special kind of learning, in the course of which the original performance process is replaced or bridged-across by new and simpler processes. The program to the left below shows the many steps our novice portrait drawer had to take in order to draw each childish body-face. The script to the right shows only those steps that actually produce the lines of the drawing; this script has only half as many steps.

The people we call experts seem to exercise their special skills with scarcely any thought at all — as though they were simply reading preassembled scripts. Perhaps when we practice to improve our skills, we're mainly building simpler scripts that don't engage so many agencies. This lets us do old things with much less thought and gives us more time to think of other things. The less the child has to think of where to put each arm and leg, the more time remains to represent what that picture-person is actually doing.