Suppose an adult watched our child and said, I see you've built an arch. What might the child think this means? To learn new words or new ideas, one must make connections to other structures in the mind. I see you've built an arch should make the child connect the word arch to agencies embodying descriptions of both the Block-Arch and the Hand-Change phenomena — since those are what is on the child's mind.

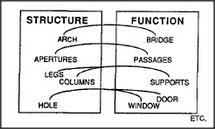

But one can't learn what something means merely by tying things to names. Each word-idea must also be invested with some causes, actions, purposes, and explanations. Consider all the things a word like arch must mean to any real child who understands how arches work and how they're made, and all the ways one can use them! A real child will have noticed, too, that arches are like variants of many other things experienced before, like bridge without a road, wall with door, tablelike, or shaped like an upside-down U. We can use such similarities to help find other things to serve our purposes: to think of an arch as a passage, hole, or tunnel could help someone concerned with a transportation problem; describing an arch as top held up by sides could help a person get to something out of reach. Which kind of description serves us best? That depends upon our purposes.

Among our most powerful ways of thinking are those that let us bring together things we've learned in different contexts. But how can one think in two different ways at once? By building, somewhere inside the mind, some arches of a different kind:

Is that a foolish metaphor — to talk of building bridges between places in the mind? I'm sure it's not an accident that we so often frame our thoughts in terms of familiar spatial forms. Much of how we think in later life is based on what we learn in early life about the world of space.