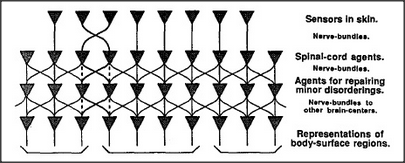

The reason our skin can feel is because we're built with myriad nerves that run from every skin spot to the brain. In general, each pair of nearby places on the skin is wired to nearby places in the brain. This is because those nerves tend to run in bundles of parallel fibers — more or less like this:

Each sensory experience involves the activity of many different sensors. In general, the greater the extent to which two stimuli arouse the same sensors, the more nearly alike will be the partial mental states those stimuli produce — and the more similar those stimuli will seem, simply because they'll tend to lead to similar mental consequences.

Other things being equal, the apparent similarity of two stimuli will depend on the extent to which they lead to similar activities in other agencies.

The fact that the nerves from skin to brain tend to run in parallel bundles means that stimulating nearby spots of skin will usually lead to rather similar activities inside the brain. In the next section we'll see how this could enable an agency inside the brain to discover the spatial layout of the skin. For example, as you move a finger along your skin, new nerve endings are stimulated — and it is safe to assume that the new arrivals represent spots of skin along the advancing edge of your finger.

Given enough such information, a suitably designed agency could assemble a sort of map to represent which spots are close together on the skin. Because there are many irregularities in the nerve-bundle pathways from skin to brain, the agencies that construct those maps must be able to tidy things up. For example, the mapping agency must learn to correct the sort of crossing-over shown in the diagram. But that is only the beginning of the task. For a child, learning about the spatial world beyond the skin is a journey that stretches over many years.