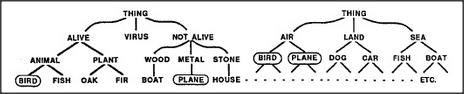

Isn't it interesting how often we find ourselves using the idea of level? We talk about a person's levels of aspiration or accomplishment. We talk about levels of abstraction, levels of management, levels of detail. Is there anything in common to all the level-things people talk about? Yes: they each appear to reflect some way to organize ideas — and each seems vaguely hierarchical. Usually, we tend to think that each of those hierarchies illustrates some kind of order that exists in the world. But frequently those orderings come from the mind and merely appear to belong to the world. Indeed, if our theory of K-line trees is correct, it would seem natural for us to classify things into levels and hierarchies — even when this does not work out perfectly. The diagram below portrays two ways to classify physical objects.

These two hierarchies split things up in different ways. The birds and airplanes are close together on one side, but far apart on the other side. Which classification is correct? Silly question! It depends on what you want to use it for. The one on the left is more useful for biologists, and the one on the right is more useful for hunters.

How would you classify a porcelain duck, a pretty decorative toy? Is it a kind of bird? Is it an animal? Or is it just a lifeless piece of clay? It makes no sense to argue about it: That's not a bird! Oh, yes, it is, and it is also pottery. Instead, we frequently use two or more classifications at the same time. For example, a thoughtful child can play with a porcelain duck as though it were a make-believe animal, yet at the same time treat it carefully, in its role as a delicate object.

Whenever we develop a new skill or extend an old one, we have to emphasize the relative importance of some aspects and features over others. We can place these into neat levels only when we discover systematic ways to do so. Then our classifications can resemble level-schemes and hierarchies. But the hierarchies always end up getting tangled and disorderly because there are also exceptions and interactions to each classification scheme. When attempting a new task, we never like to start anew: we try to use what has worked previously. So we search around inside our minds for old ideas to use. Then, when part of any hierarchy seems to work, we drag the rest along with it.