Now let's ask Mary to describe herself — to tell us everything she can about her shape and weight and size and strength, her dispositions and her traits, her accomplishments and ambitions, wishes, fears, possessions, and so on. What might be the general character of what we'd hear? At first it would be hard to assemble any coherent sense of all those details. But gradually we'd notice that various groups of items were closely related, while others were rarely mentioned in connection with one another. Little by little, we would discern structure and organization in what Mary had said, and finally we'd start to see the outlines of at least two different mental realms.

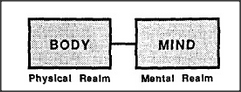

Now, what would happen if we asked Mary to speak not about specific things, but about the general subject of What kind of entity am I? Since she has no direct way to examine her entire self, she can only summarize what she can discover about her mental model of herself. In doing so, she'll probably find that almost everything she knows appears to lie in two domains, with relatively little in between. This means that Mary's model of her model of herself will have an overall dumbbell shape, one side of which represents her physical self, the other side of which represents her psychological self.

Do people go on to make models of their models of their models of themselves? If we kept on doing things like that, we'd get trapped in an infinite regress. What saves us is that we get confused and lose track of the distinctions between each model and the next — just as our language-agencies lose track when they hear about the rat that the cat that the dog worried killed. The same thing must happen whenever we ask ourselves questions like Did John know that I knew that he knew that I knew that he knew that? And the same thing happens whenever we try to probe into our own motivations by continually repeating, What was my motive for wanting that?

Eventually, we simply stop and say, Because I simply wanted to. The same when we find things hard to decide: we can simply say, I just decide, and this can help us interrupt what otherwise might be an endless chain of reasoning.