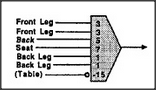

There are important variations on the theme of weighing evidence. Our first idea was just to count the bits of evidence in favor of an object's being a chair. But not all bits of evidence are equally valuable, so we can improve our scheme by giving different weights to different kinds of evidence.

How could we prevent this chair recognizer from accepting a table that appeared to be composed of four legs and a seat? One approach would be to try to rearrange the weights to avoid this. But if we already possessed a table recognizer, we could use its output as evidence against there being a chair by adding it in with a negative weight! How should one decide what number weights to assign to each feature? In 1959, Frank Rosenblatt invented an ingenious evidence-weighing machine called a Perceptron. It was equipped with a procedure that automatically learned which weights to use from being told by a teacher which of the distinctions it made were unacceptable.

All feature-weighing machines have serious limitations because, although they can measure the presence or absence of various features, they cannot take into account enough of the relations among those features. For example, in the book Perceptrons, Seymour Papert and I proved mathematically that no feature-weighing machine can distinguish between the two kinds of patterns drawn below — no matter how cleverly we choose the weights.

Both drawings on the left depict patterns that are connected — that is, that can be drawn with a single line. The patterns on the right are disconnected in the sense of needing two separate lines. Here is a way to prove that no feature-weighing machine can recognize this sort of distinction. Suppose that you chopped each picture into a heap of tiny pieces. It would be impossible to say which heaps came from connected drawings and which came from disconnected drawings — simply because each heap would contain identical assortments of picture fragments! Every heap would contain exactly four pictures of right-angle turns, two line endings, and the same total lengths of horizontal and vertical line segments. It is therefore impossible to distinguish one heap from another by adding up the evidence, because all information about the relations between the bits of evidence has been lost.