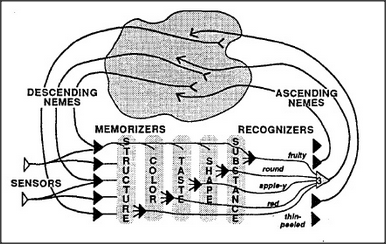

Now let's redraw the diagram for the language-agency, but fill in more details from the last few sections.

Something amazing happens when you go around a loop like this! Suppose you were to imagine three properties of an apple — for example, its substance, taste, and thin-peeled structure. Then, even if there were no apple on the scene — and even if you had not yet thought of the word apple — the recognition-agent on the left will be aroused enough to excite your apple polyneme. (This is because I used the number three for the required sum in the apple polyneme's recognizer instead of demanding that all five properties be present. ) That agent can then arouse the K-lines in other agencies, like those for color and shape — and thus evoke your memories of other apple properties! In other words, if you start with enough clues to arouse one of your apple-nemes, it will automatically arouse memories of the other properties and qualities of apples and create a more complete impression, simulus, or hallucination of the experience of seeing, feeling, and even of eating an apple. This way, a simple loop machine can reconstruct a larger whole from clues about only certain of its parts!

Many thinkers have assumed that such abilities lie beyond the reach of all machines. Yet here we see that retrieving the whole from a few of its parts requires no magic leap past logic and necessity, but only simple societies of agents that recognize when certain requirements are met. If something is red and round and has the right size and shape for an apple — and nothing else seems wrong — then one will probably think apple.

This method for arousing complete recollections from incomplete clues — we could call it reminding — is powerful but imperfect. Our speaker might have had in mind not an apple, but some other round, red, fruit, such as a tomato or a pomegranate. Any such process leads only to guesses — and frequently these will be wrong. Nonetheless, to think effectively, we often have to turn aside from certainty — to take some chance of being wrong. Our memory systems are powerful because they're not constrained to be perfect!